<< Go Back up to Region ‘United Kingdom: outside London’

| Follow Mike Hume’s Historic Theatre Photography: |  |

|

Architects: Campbell Douglas & Sellars

First Opened: 28th December 1878 (147 years ago)

Reopened as the Citizens’ Theatre: 11th September 1945

Closed for Renovation: June 2018

Reopened After Renovation: 23rd August 2025

Former Names: Her Majesty’s Theatre and Royal Opera House, Royal Princess’s Theatre

Website: www.citz.co.uk

Telephone: 0141 429 0022

Address: 119 Gorbals St, Glasgow, G5 9DS

The Citizens Theatre first opened as Her Majesty’s Theatre and Royal Opera House in December 1878, and was the first theatre in Glasgow to be built on the south side of the River Clyde. It is notable for having retained much of its elaborate nineteenth century stage machinery, the only original example of its kind throughout provincial theatres across the UK.

Detailed Information

Detailed Information

The theatre was built by John Morrison of Morrison & Mason Ltd (also responsible for building the City Chambers, The People’s Palace, Merchants House, and the King’s Theatre all in Glasgow), and opened in late December 1878 under the management of James F. McFadyen. While the theatre’s name was overly-long and pretentious – something which did not escape the attention of the press at the time – it did allude to the intent to stage high class productions. Elaborate stage machinery was included to enable the execution of theatrical effects to rival any of the larger theatres, in Glasgow or beyond.

The theatre was designed by architects Campbell Douglas and James Sellars. Their firm, Campbell Douglas & Sellars, did not generally design theatres, their primary focus being provincial municipal architecture. Seating capacity was something over 2,000 – probably 2,500, although in 1912 it was officially listed as 2,700.

The Citizens Theatre is a complex building having undergone many changes and additions over the years, although the main features of the 19th century auditorium and stagehouse remain largely intact and unaltered.

The building’s original façade was constructed using components salvaged from the Union Bank on Ingram Street (now The Corinthian Club  ): at the same time as James Morrison was building tenements and planning his new theatre in the Gorbals, the bank employed Morrison’s company to extend their premises, and the bank’s classical portico from 1841 required replacing to afford them more space at their land-locked site. Morrison salvaged the bulk of the frontispiece and had Douglas & Sellars rebuild the components into an imposing classical façade for his new theatre set within the Gorbals Street tenements. The statues which had formed the crown of the bank’s Ingram Street façade, by celebrated sculptor John Mossman, stayed at the bank, and so to complete the picture at the new theatre six statues were commissioned from Mossman: William Shakespeare and Robert Burns booked-ended four statues representing the Muses of Tragedy, Comedy, Music, and Dance/Burlesque.

): at the same time as James Morrison was building tenements and planning his new theatre in the Gorbals, the bank employed Morrison’s company to extend their premises, and the bank’s classical portico from 1841 required replacing to afford them more space at their land-locked site. Morrison salvaged the bulk of the frontispiece and had Douglas & Sellars rebuild the components into an imposing classical façade for his new theatre set within the Gorbals Street tenements. The statues which had formed the crown of the bank’s Ingram Street façade, by celebrated sculptor John Mossman, stayed at the bank, and so to complete the picture at the new theatre six statues were commissioned from Mossman: William Shakespeare and Robert Burns booked-ended four statues representing the Muses of Tragedy, Comedy, Music, and Dance/Burlesque.

Moving into the interior, the auditorium is on three levels. The Stalls (main floor level) would have originally been separated into Stalls (front) and Pit (rear), the latter for the lower classes and fitted out with simple wooden benches for seating. The two balconies can be loosely described as horseshoe shaped, however more specifically they are shaped like a lyre. The balconies are supported on slender pillars with relatively large capitals. The Dress Circle (first level above the Stalls) originally had just six rows of seats which must have afforded generous legroom to the upper class patrons who sat there. The Upper Circle (second level above the Stalls) was – and still is – bisected by a cross-aisle, the front six rows of seats originally being called the Amphitheatre and the rear section being physically segregated from the rest of the Upper Circle, called the Gallery, and consisting of simple bench seating for the lower classes.

Boxes at Stalls and Dress Circle level flank the stage and indeed provide the sides of the proscenium arch – there is no proscenium framing. Close inspection suggests that the boxes in their present form may have been a later addition. They could have been added as early as 1879, when the theatre closed – less than a year after it opened – for “considerable alteration and redecoration”. The boxes are surmounted by caryatids reminiscent of the four Muses originally mounted atop the building’s façade.

The auditorium features non-original air vents which were designed to match architectural elements found throughout the auditorium. These vents date from the 1945/46 refurbishments which took place after the Citizens’ Theatre Company took up residence at the theatre.

The auditorium has a largely flat and plain ceiling with deep coving arching down to the side walls. It is noticeable that the architectural decoration stops in line with the cross-aisle at Upper Circle level, the divider for the Gallery and its lower class bench seating. The medallion in the center of the ceiling, now sporting a historically inaccurate chandelier, would have originally housed a sunburner. Sunburners were dual light and ventilation devices which employed gas burners for light surrounded by vents, in the form of ornamental grilles, to expel foul air. The gas burners heated the ambient air resulting in convection currents which pulled foul air up into the sunburner which then vented out of the building through an exhaust duct running through the attic/roof void. Although the sunburner device has long since been removed it is clear to see how the device was fitted, and the remnants of its exhaust, in the attic above the auditorium.

The stage was fitted with an array of impressive stage machinery both above and below the stage. The nineteenth century substage machinery is the last surviving original installation of any provincial theatre in the UK. A comparable and original installation exists at Her Majesty’s Theatre in London, currently home to Andrew Lloyd Webber’s “The Phantom of the Opera”  . The Gaiety Theatre on the Isle of Man, and the Tyne Theatre & Opera House in Newcastle upon Tyne both house similar substage machinery however are mostly non-original reconstructions.

. The Gaiety Theatre on the Isle of Man, and the Tyne Theatre & Opera House in Newcastle upon Tyne both house similar substage machinery however are mostly non-original reconstructions.

The stage was laid out along the established principles of UK theatres at the time, which noted architect and engineer Edwin O. Sachs described as the “English Wood Stage”. The main stage area had a number of bridges (elevators), extending the width of the stage and 2-3ft deep front-to-back. There were three such bridges at this theatre. The bridges were interspersed with “cuts”, narrow slots the same width as the bridges which allowed two-dimensional scenery to be raised on wooden tracks called “sloats” immediately in front of and behind the bridges. Downstage, lost after alterations made in the 1950s, was a “grave trap” located downstage center and two “corner traps” located downstage right and left.

The overstage machinery consisted of two drum and shaft mechanisms which allowed a single operator to effect an entire scene change single-handedly. Multiple backdrops and cut cloths would be roped back to a long wooden shaft above the stage, operated by a line wrapping around a large diameter drum (to afford mechanical advantage) connected to the shaft. By roping the backdrops and cut cloths up and down the stage onto the shaft in different directions at various points along its length, the drum and shaft mechanism could be used to achieve wholesale transformations from one scene to another under the control of a single operator.

Unfortunately the complex stage machinery may have been a little too much to handle, or the staff assembled to work it not quite experienced enough, as the theatre’s opening night production of “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves” on 28th December 1878 did not go well. The local press described the scenery as being “in a state of mechanical rebellion”, with the staff failing more than once to bring it under control. The theatre was crammed for the opening night with an expectant and jubilant crowd, and after repeated issues their collective patience grew thin, particularly when there was a delay of 30 minutes for the transformation scene. Mrs McFadyen (the actress Carry Nelson, who appeared in the pantomime as principal boy) appealed to the audience but was largely ignored, and the audience started to throw objects at the stage and performers. Ultimately the safety/fire curtain was lowered at which point seat cushions were thrown at it!

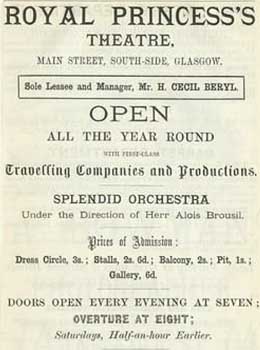

The McFadyens had a short run at the theatre; the Glasgow Herald of 12th July 1879 reported that, as a result of a case raised by John Morrison (the builder of the theatre), a warrant for “Ejection of a Lessee” had been issued in McFadyen’s name for having become notour bankrupt. A month later the theatre was being managed by George H. Burnside, however by mid-September 1879 it closed, with rumors suggesting it would reopen soon under the management of H. Cecil Beryl.

In December 1879 the theatre reopened having “undergone considerable alteration and redecoration”. It was rechristened the Royal Princess’s Theatre and was indeed under the management of H. Cecil Beryl. Opening night was 20th December 1879 with the drama “New Babylon” by Paul Meritt and direct from London. A diet of melodrama, variety, and pantomime would sustain the theatre for many years to come.

In 1886 Beryl moved to a different theatre in Glasgow and his business partner of the time, Rich Waldon, assumed management of the Royal Princess’s Theatre. Backstage areas were expanded in 1894 with the addition of further buildings to the rear which included a scenic paint shop with two paint frames. The Victorian paint frames still exist and are a rarity in the 21st century. The paint frames are in constant use for painting backdrops and other scenic elements.

In 1897 Waldon bought the theatre from its builder, John Morrison. Waldon had interests in several other theatres however worked tirelessly to make the Royal Princess’s a successful family theatre. Upon Waldon’s death in 1922 he bequeathed the theatre to Harry McKelvie, a trusted colleague and manager of several of Waldon’s theatres, also a successful producer of popular pantomimes including some of Waldon’s own writing. McKelvie maintained a programme of live entertainment at the theatre during a period when many theatres succumbed to the sweep of cinema across the country.

In 1944 McKelvie started planning for his retirement and offered to lease the theatre to James Bridie. Bridie was one of the founders of the Glasgow Citizens’ Theatre Company, started two years prior in 1943 and performing at the Athenaeum Theatre in Buchanan Street (owned by the Scottish College of Music, a predecessor of the modern day Royal Conservatoire of Scotland  ). With a desire for their own performance space and the offer of very agreeable lease terms (ten years at £1,000 per year) the Citizens’ Theatre Company moved into the theatre.

). With a desire for their own performance space and the offer of very agreeable lease terms (ten years at £1,000 per year) the Citizens’ Theatre Company moved into the theatre.

Despite some immediate redecoration and seat improvement requirements before performances could take place, the theatre opened as the Citizens’ Theatre on 11th September 1945 with a performance of J.B. Priestley’s “Johnson Over Jordan”. The initial 10-year lease at the theatre was a success. Approaching the end of the term the Citizens’ Theatre Company made the bold move of lobbying the Glasgow Corporation (the City of Glasgow) to purchase the building for them outright. The City ultimately bought the theatre from the McKelvie family and leased it back to the Citizens’ Theatre Company.

In the 1950s a new safety/fire curtain was installed, and at the same time a brick firewall was built at the stage mezzanine level (immediately below the stage) to complement the safety curtain and complete the fire separation of auditorium from stagehouse. The new wall rendered the downstage grave and corner traps obsolete, although it is likely they had already been out of use for quite some time.

The 1960s and 1970s were trying times for the theatre and its company and at one point flat-rate admission of 50 pence was introduced to attract audiences.

In 1977 Sellars’ imposing classical façade, transplanted from the Union Bank on Ingram Street 90 years earlier, was demolished when the tenements surrounding it were condemned. Quick-thinking theatre staff saved the six Mossman statues from the façade. A functional but lackluster entrance building to the theatre followed. The auditorium was given a bold new color scheme of red and green with gold highlights. The stage extended outward with a sizable thrust stage over what had been the orchestra pit.

In the late 1980s the Front-of-House facilities were again extensively reworked resulting in a foyer/lobby with impressive glass apex ceiling. The six Mossman statues were put on display in the foyer. A counterweight scenery flying system was installed in the stagehouse. In the auditorium the rear of the Upper Circle (originally the Gallery) was brought forward by building a wall which closed-off the rearmost seats, and the theatre reopened on 2nd February 1990 with a production of “Enrico Four”. It was at this time that the current stippled-gold-over-red color scheme was applied to the auditorium, replacing the bold block colors of the late 1970s, and lines of tightly-packed clear electric lamps were run around the circles. These rows of shining lamps have come to be an enduring and much-loved iconic symbol of the modern Citizens Theatre.

In 1997, National Lottery Funding paid for building work to add lifts/elevators both backstage and Front-of-House, wheelchair access, a new stage door entrance, and a large scale rehearsal room.

In late June 2018 the theatre held its last performances before closing to break ground on its long-planned and ambitious £21.5 million redevelopment project to enlarge and modernize the building while preserving its history for future generations. The theatre originally planned to reopen in 2021, however due to the COVID-19 pandemic and knock-on effects the theatre reopened in August 2025. Improvements include:

As noted in the redevelopment project’s Design & Access Statement, the Citizens Theatre considers the heritage and historic stage machinery to be an important part of their heritage and identity as a theatre company, and is particularly keen that elements can be restored to working condition, made accessible to the public, and demonstrated and understood. It should be noted that it is unlikely the machinery could ever be used in a modern production, and this is not the intention of the restoration work. Specific work includes:

The Citz reopened on Saturday 23rd August 2025, the first day of a two-week “Homecoming Festival” packed full of interactive events, tours, and performances. The first production following reopening is “Small Acts of Love” by Frances Poet and Ricky Ross, a Citizens Theatre production in association with the National Theatre of Scotland. Performances begin 9th September 2025.

It is unknown when the theatre and its company changed from being Citizens’ to Citizens (sans apostrophe), but it is of little consequence in the grand scheme of the excellent work the company brings to its beloved 140-year-old theatre, the citizens of Glasgow, the people of Scotland, and far beyond.

Notable people who have performed or worked at the Citizens Theatre include Stanley Baxter, Sean Bean, Pierce Brosnan, Robbie Coltrane, Tim Curry, Celia Imrie, Glenda Jackson, Fulton Mackay, Allison McKenzie, Una McLean, Gary Oldman, Alan Rickman, Tim Roth, Mark Rylance, Molly Urquhart, Sophie Ward, and Trisha Biggar (Costume Designer for “Star Wars” Episodes I-III), who was for very many years the Wardrobe Mistress at the Citizens Theatre.

Video from our YouTube channel:

Video from our YouTube channel: Listed/Landmark Building Status

Listed/Landmark Building Status (15th December 1970)

(15th December 1970) How do I visit the Citizens Theatre?

How do I visit the Citizens Theatre?The theatre runs a series of Heritage Building Tours as part of their Heritage and Homecoming programme. Tours are held regularly, last 90 mins, and cost approximately £8. Full details including online booking and details of audio described tours are available at the theatre’s Heritage Building Tours  page.

page.

The theatre also generally participates in Glasgow Doors Open Day  , usually held mid-September each year.

, usually held mid-September each year.

Further Reading

Further Reading contains information about the theatre and theatre company, online calendar and booking, and additional information on the 2019-2021 redevelopment project.

contains information about the theatre and theatre company, online calendar and booking, and additional information on the 2019-2021 redevelopment project. , the premier Music Hall and Theatre History website in the UK.

, the premier Music Hall and Theatre History website in the UK. in the Dictionary of Scottish Architects.

in the Dictionary of Scottish Architects. contains further information and photos not seen elsewhere.

contains further information and photos not seen elsewhere. .

. contains 250 detailed photos of the theatre.

contains 250 detailed photos of the theatre. , as featured on the BBC.

, as featured on the BBC. and Part 2

and Part 2  . Also check out his earlier visit from August 2017

. Also check out his earlier visit from August 2017  when he found out about the history of the Citizens Theatre with Production Manager Graham Sutherland.

when he found out about the history of the Citizens Theatre with Production Manager Graham Sutherland. , a 9th March 2025 feature in The Sunday Post as the theatre nears its reopening.

, a 9th March 2025 feature in The Sunday Post as the theatre nears its reopening. , published 5th June 2025 in LSi Online

, published 5th June 2025 in LSi Online  .

. , published by BBC News on 23rd August 2025.

, published by BBC News on 23rd August 2025. , by Christopher Brereton, David F. Cheshire, John Earl, Victor Glasstone, lain Mackintosh, and Michael Sell, published by John Offord (Publications) Limited. ISBN 0903931427.

, by Christopher Brereton, David F. Cheshire, John Earl, Victor Glasstone, lain Mackintosh, and Michael Sell, published by John Offord (Publications) Limited. ISBN 0903931427. , by Bruce Peter, published by Polygon. ISBN 0748662618.

, by Bruce Peter, published by Polygon. ISBN 0748662618. , by John Earl & Michael Sell, published by A&C Black. ISBN 0713656883.

, by John Earl & Michael Sell, published by A&C Black. ISBN 0713656883. Technical Information

Technical Information Photos of the Citizens Theatre

Photos of the Citizens TheatrePhotographs copyright © 2002-2026 Mike Hume / Historic Theatre Photos unless otherwise noted.

Text copyright © 2017-2026 Mike Hume / Historic Theatre Photos.

For photograph licensing and/or re-use contact us here  . See our Sharing Guidelines here

. See our Sharing Guidelines here  .

.

| Follow Mike Hume’s Historic Theatre Photography: |  |

|